REC and neurodiversity specialists Uptimize's guide on how to recruit neurodiverse candidates

Practical guides

Introduction

All candidate pools are by definition neurodiverse, in that they contain people with naturally different brains (there is no one “normal” brain). Given how common neurodivergence is, talent pools are likely to include neurodivergent candidates (whether or not those applicants choose to disclose, have a medical diagnosis, or sense of neurodivergent identity).

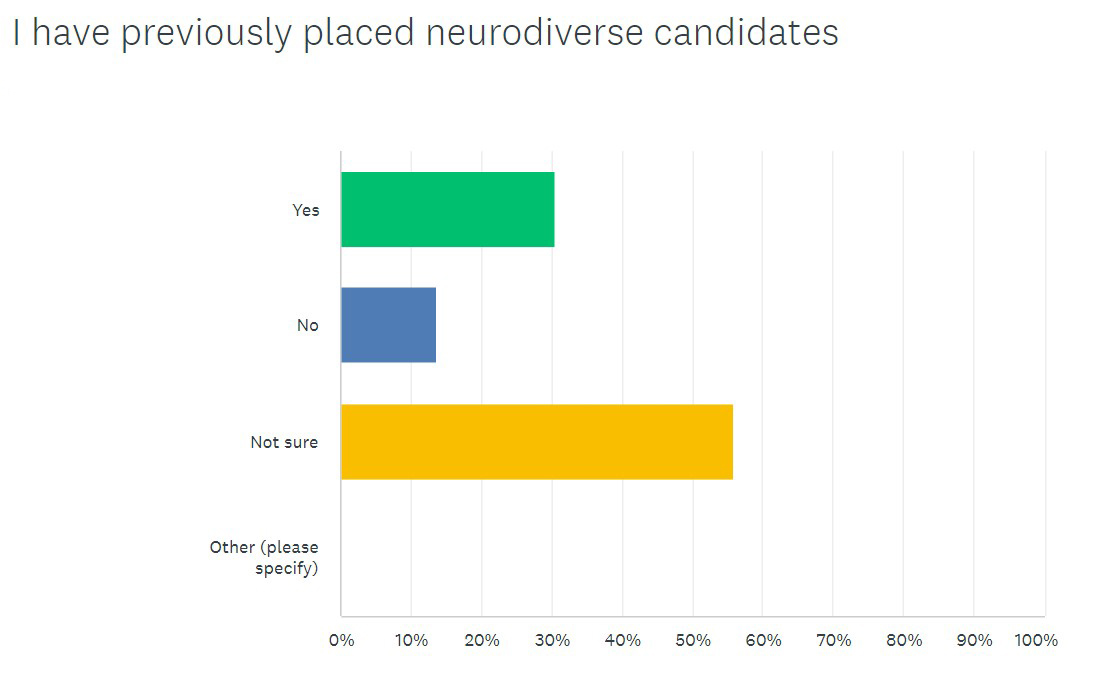

This short guide, produced in partnership with Uptimize, provides an introduction on how you can recruit neurodiverse talent. You’ll see where other recruiters like you find themselves with this topic in 2023 - often, with a base awareness and enthusiasm for the potential of neurodiverse talent, but without the experience or tools to feel confident in delivering neuroinclusive hiring outcomes. Interestingly, only 30% of recruiters in our study have knowingly placed neurodivergent candidates. This is likely to be because of a lack of familiarity with the topic, as well as candidates not disclosing the information because of potential judgement or misunderstanding.

To help move the conversation forward, you’ll also find in this guide Uptimize’s latest (January 2023) glossary of key related terms, some tips on working – and recruiting – more neuroinclusively, and suggestions for how you can help bring the topic of neuroinclusion to your organisation and team.

The PDF of the guide to recruiting neurodiverse talent is also available to download.

Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (“EDI”) initiatives in business have a long history, having originated as long ago as the 1960s. Emerging from the 2010s, studies have found that the impact of EDI on businesses’ success is remarkable. The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) Diversity and Inclusion Survey discovered that companies with above average diversity scores were nearly 20% more innovative . The Deloitte study also revealed that inclusive companies are twice as likely to meet or exceed financial targets. In this section we explore how the recruitment sector addresses EDI and identify its main challenges.

In autumn 2022, the REC and Uptimize surveyed a pool of members to determine familiarity and comfort levels on the topic of neurodiversity in recruitment. The findings are below.

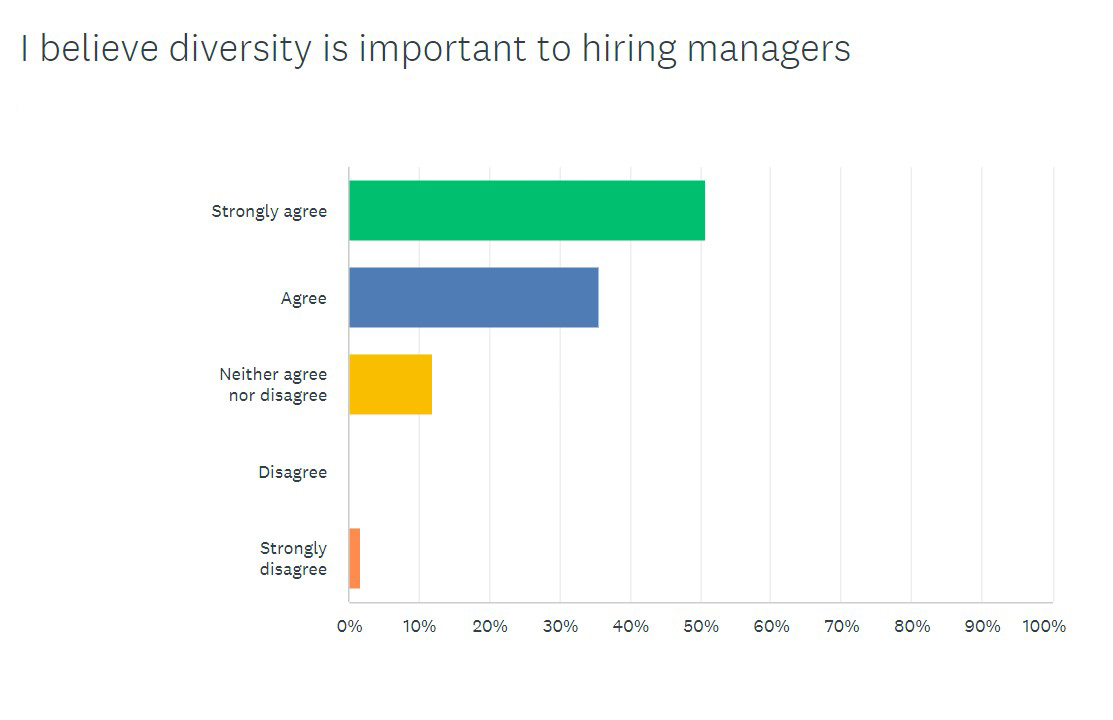

Today, most organisations and leaders commit to implementing EDI policies. They often emphasise greater “diversity of thought”, creativity and innovation, and the power of inclusion to drive greater engagement and talent retention. Many firms also publish diversity data annually, showing an openness in their progress and commitment to improvement. No surprise, then, that recruiters in our study overwhelmingly (87%) believed that diversity was important to hiring managers.

Neurodiversity at work

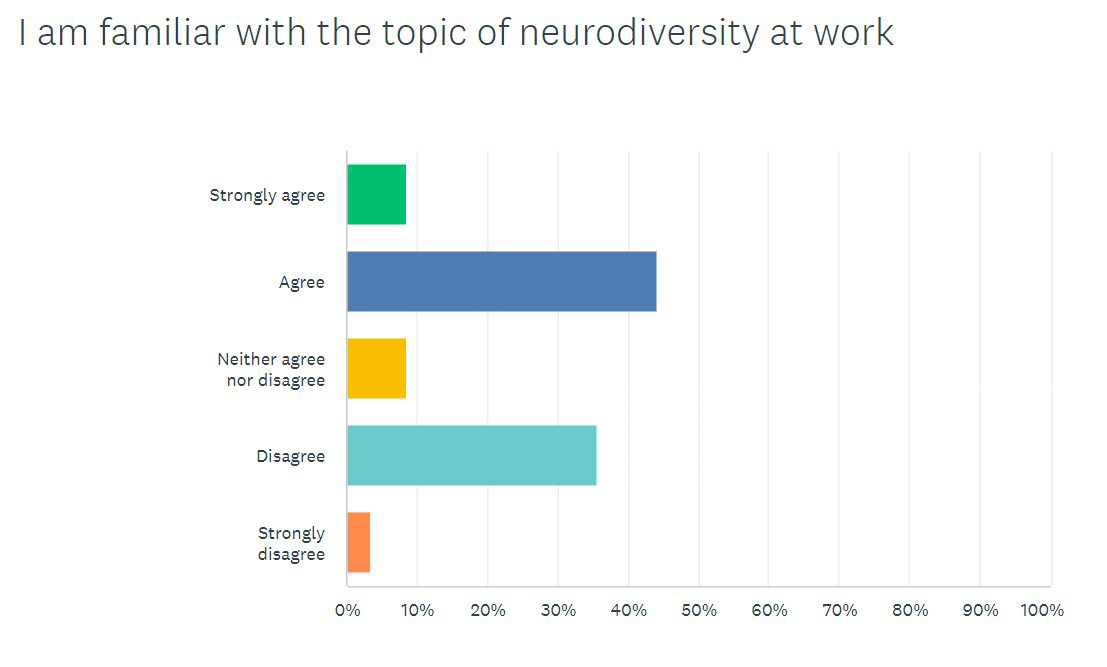

As shown above, understanding diversity at work is mixed among recruiters. While 52% are familiar with the topic, 39% are not. Neurodiversity at work has often been overlooked in the EDI sphere, with greater focus on more visible differences such as gender, race or ethnicity. In fact, the term “neurodiversity” wasn’t coined until the 1990s. Today, neurodiversity still doesn’t often appear in corporate careers websites or in EDI reporting.

However, progress is being made. Neurodiversity in workplaces is gaining greater recognition because of better societal awareness of neurodivergence. This has largely been driven by increasing diagnostic rates, the self-advocacy of neurodivergent celebrities, and business initiatives to attract, hire and retain talent who think differently. Pioneering “autism hiring programmes”, such as those launched by EY, JPMorgan Chase and SAP in the 2010s shows corporate enthusiasm for different thinking styles and recognition of the positive impact neurodivergent talent can deliver. JPMorgan Chase, for example, found that its neurodivergent hires could be as much as 140% more productive than their peers demonstrating why this is such an important issue for recruiters.

According to the REC’s 2022 autumn survey, recruiters’ familiarity of hiring neurodiverse talent was varied. Just over half (52%) described themselves as familiar, showing the growing interest in neurodiversity, but also highlighting the need for further progress in this area.

The untapped potential: neuroinclusion

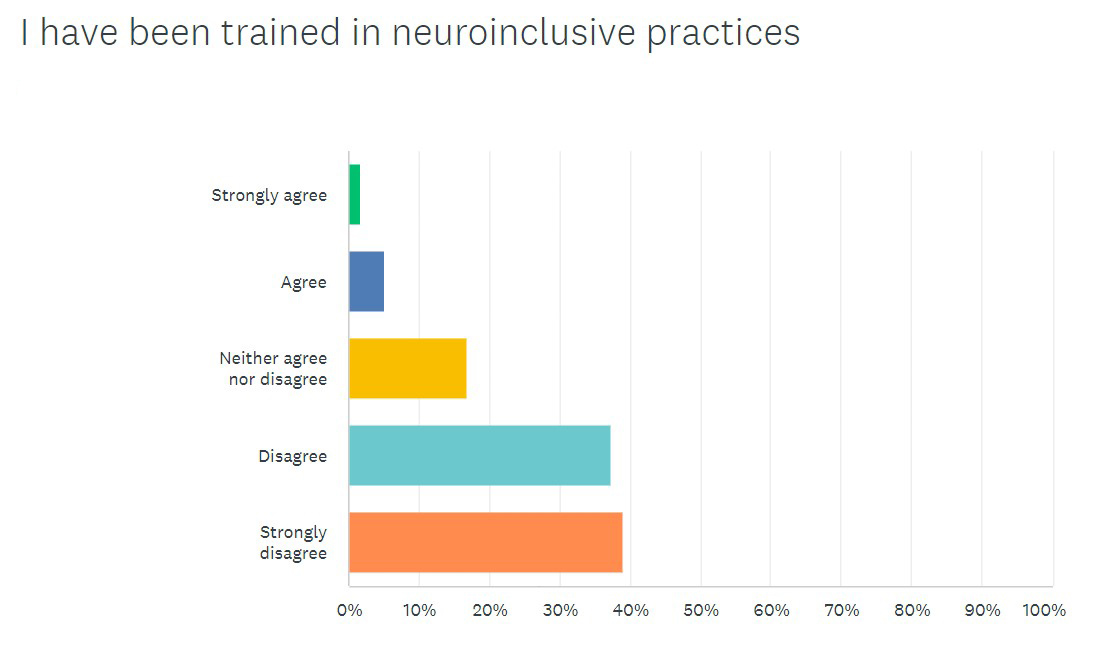

While almost half of surveyed recruiters are familiar with the topic of neurodiversity at work, there is a significant gap in practical knowledge and that’s what this guide aims to address. Almost 80% of respondents said they had received no training on neuroinclusive recruitment and only 20% understood how to conduct a neuroinclusive interview.

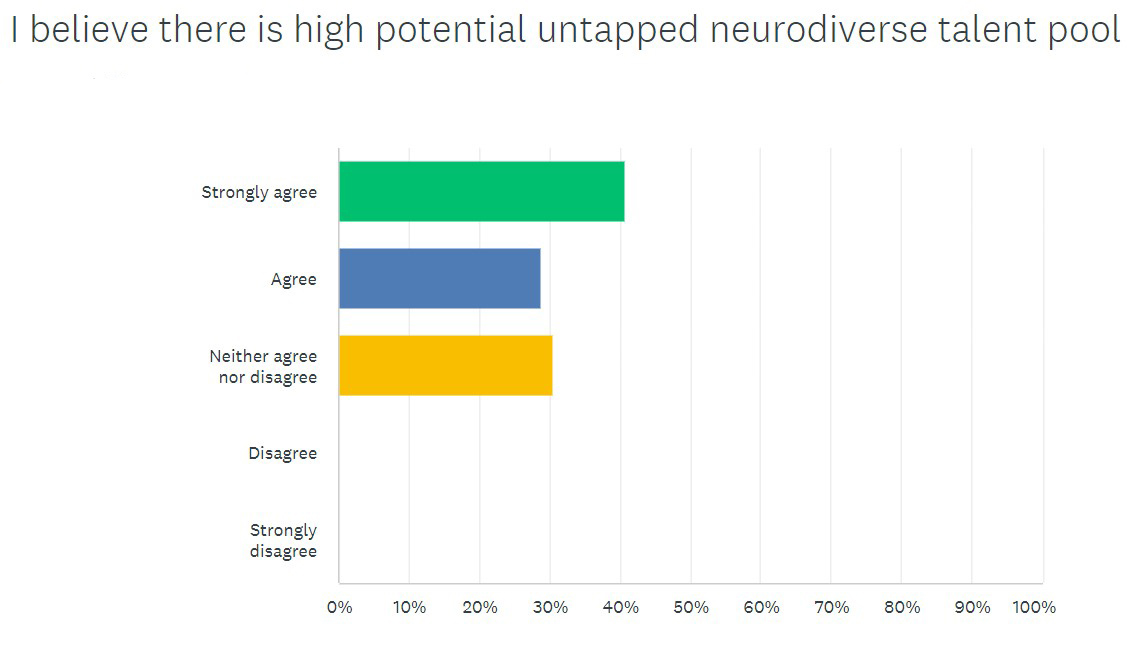

Despite patchy familiarity with the topic, the majority of recruiters surveyed agreed (70%) on the potential value of different thinkers at work. This finding shows that neurodivergent talent pools risk remaining “untapped” because of a lack of knowledge, confidence, or barriers in conventional hiring processes.

Placements

Our 2022 autumn survey also showed a lack of awareness around whether candidates were neurodiverse, with more than half (56%) of respondents unsure if they had previously placed a neurodiverse candidate.

This shows why the very hidden nature of neurodiversity can be a challenge for hirers. Neuro-differences are far less visible than other diversity characteristics, and a considerable majority of neurodivergent people choose not to disclose this information in the interview process or even in employment for fear of negative repercussions. We’ll explore what recruiters can do to address this type of issue in section 3.

Neurodiversity in hiring processes

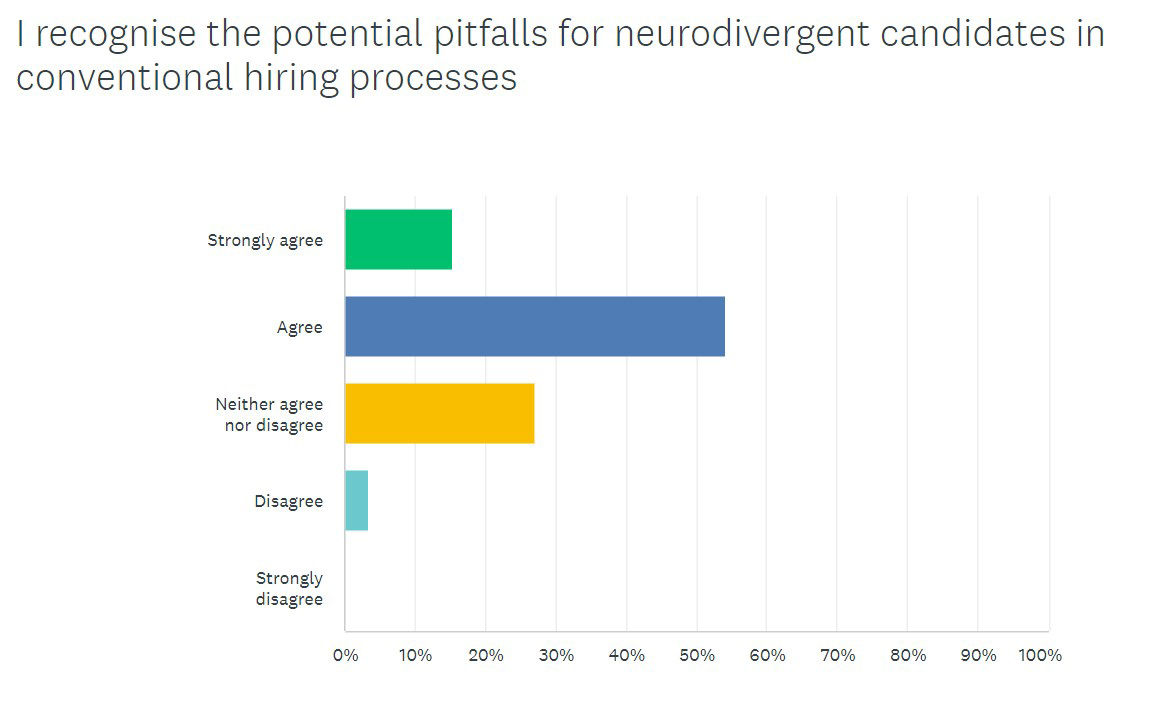

Despite acknowledging the often-untapped potential of neurodivergent talent, a significant number of recruiters surveyed (69 %) acknowledged that barriers often exist in the recruitment process for neurodivergent candidates. This shows there are obstacles that lead to unintentional exclusions of such talent in conventional hiring processes with just 7% of recruiters surveyed having received training or guidance on this.

As highlighted by the survey results, building awareness of neurodiversity at work, and importantly, using that understanding to take demonstrable action is essential in improving EDI in the recruitment industry. The core message to clients should be if you put EDI at the core of your people plan, your organisation will be in a more competitive position, particularly important in a tight labour market. However, recruiters need to be the people leading by example and sharing that message.

Neurodiversity exists in every workplace. Every team member brings their own unique brain wiring and information processing style to work. This means that every interaction at work – between managers and direct reports, recruiters and candidates, or simply between colleagues – is an opportunity to practice neuroinclusion.

However, many neurodivergent professionals report the barriers they face when seeking employment and at work. This can include snap judgments of differences in how someone presents – for example, a candidate’s flatter tone in their speaking voice could be wrongly construed by hiring managers as a lack of genuine interest or passion. The absence of neurodiversity education or training often impacts people’s perceptions and responses. As such, neurodivergent candidates and staff are unable to reach their full potential.

Neuroinclusivity in Recruitment

It’s important to remember that recruitment begins long before the candidates fill out the application. Job sites often talk about commitments to diversity and inclusion, but neurodiversity or neuroinclusion are often left out of the conversation. For employers, a lack of branding to show the organisation welcomes different thinkers could be a barrier for neurodiverse candidates when they apply for a position.

The next is the application interface itself. For instance, vague job descriptions are a major challenge. Application forms can be poorly formatted and needlessly timed, which increases stress. Psychometric tests are also a particular irritation for many neurodivergent candidates due to what can come across as illogical and confusing questioning. The latter have been famously described by one neurodivergent self-advocate, Rudy Simone, as being “like a bouncer at the door of a nightclub that doesn’t let us in because we’re unfashionable” . But progress is being made with many businesses in this field now seeking to build in neurodivergent testing and input at the design stage.

Candidates who pass the application stage will usually then face an interview. These are tests of verbal and social performance – something that will suit some people more than others. Interviews are likely to remain central to application processes, but they can be made significantly more inclusive if those conducting them have a core awareness of neurodiversity and use this to keep common biases in check.

This can include:

- checking for candidate comfort at the start of any in-person interview

- avoiding multiple interviewers rapid-fire questioning (which can be disorienting and stressful for some)

- asking clearer questions – for example, try ‘what is your top priority for your professional growth and development?’ over the commonly asked ‘where do you see yourself in X years’ time?’).

Addressing these challenges requires a basic awareness of neurodiversity. That means combating biases internally and externally, at work or during the hiring process. Maximum productivity is likely to be achieved only when individuals can work to their own strengths through their own style.

Neuroinclusivity in Management

Although line managers have a direct and crucial impact on their reports, many are often unaware that they manage a neurodiverse person or team. As such, many are reluctant to tailor their management style and processes accordingly. This can result in miscommunication, tension, unfinished tasks, and delays. The lack of knowledge about neurodiversity can also have a negative impact on collaboration, with neurodivergent employees often finding their needs and preferences ignored.

The key is to speak to your team members in a safe and non-judgemental way about how they would like to receive instructions. You’ll get different answers based on the person’s information processing style which will help you work together effectively.

Neuroinclusivity in Communication

Communication preferences differ, yet team norms can result in a “majority rules” approach where the communication channels used are preferred by some but not others. Poorly communicated tasks or unclear priorities can be particularly challenging for neurodivergent professionals who may experience difficulties with planning and short-term memory. Some may find certain document or spreadsheet formats particularly hard to process, especially if there are multiple versions of one document, leading to reduced productivity.

The key is to understand what way of communicating and presenting information is best for your team and the individuals within it, then you can try to adapt processes to reflect this.

Neuroinclusivity in Meetings

Meetings conducted without neuroinclusion in mind can lead to confusion. Some colleagues may be challenged by unstructured meetings where lots of people try to speak at once. Other colleagues may find it difficult to concentrate in long meetings without breaks.

A structured meeting with a clear agenda, meeting notes, and regular short breaks can make a significant difference.

Universal design: one size does not fit all

A key concept for practising neuroinclusion is “Universal Design” – a proactive measure to ensure environments, processes, and policies benefit all. This concept originated in architecture, but it applies to the workplace too. This concept should be taken into every aspect of work as it proactively considers everyone’s needs.

Neurodivergent employees may experience particular sensory sensitivity to inputs such as bright lights or loud noises, and as a result the conventional open-plan office may be problematic for some. You should consider carefully, as a result, any space in which you conduct in person assessments – and always check for candidate comfort. For example, at the beginning of an interview, start by asking candidates “before we start, I just want to check, is this space comfortable for you?”

Managers asking their team how they would best like to plan to make sure that everyone can contribute in a way that supports them and boosts overall output is another example of Universal Design in action. As is a project lead who develops clear and inclusive guidelines for team meetings, such as the distribution of clear agendas, meeting notes and the implementation of regular short breaks.

Where to begin with neuroinclusion

You may be thinking at this point, where do I start? Here are some initial steps you can take immediately to bring neuroinclusion both to your own work and that of your organisation:

- Make an effort to practise neuroinclusion in your daily interactions with others at work, whether colleagues, direct reports, managers, or candidates. This can include being aware that you are bringing your own thinking style and preferences to such interactions… and so is everybody else. Don’t expect others to necessarily want to communicate, problem-solve or organise their work as you prefer. Instead, start conversations that help everybody to share their preferences, and don’t judge people if their way of presenting, communicating or working is different from your own. This is a valid practice regardless of if you or your teammates identify as neurodivergent. It normalises that people’s brains respond to different messaging.

- Champion the topic of neuroinclusion. Anybody can be a champion of neuroinclusion in an organisation, whatever their role. Both neurodivergent and neurotypical colleagues can be successful neuroinclusion champions. Find out what your organisation has already done in this area, if anything. Suggest that it is a topic worth focusing on - one likely to make you and your colleagues more inclusive and more effective recruiters.

- Help spark the topic. Action towards greater neuroinclusion signals to EVERYBODY in an organisation that this is important and can help people feel comfortable enough to open up about their own preferences or needs. Share your own neurodiversity journey if you feel safe and empowered to do so. Neurodiversity employee resource groups (ERGs) have become popular over the past few years - does your organisation have such a group? Perhaps you could be part of the process of creating one - you will likely find others who are also interested in the topic for their own reasons. Such groups, working with HR, can be the catalyst for training initiatives that will ultimately help catapult the organisation towards far greater neuroinclusion, and all its benefits.

- Consider neurodiversity proactively across all candidates, engage, and recognise that people will present differently and have different preferences. Also understand that individuals who may benefit from a tailored approach may not feel comfortable immediately sharing this.

Neuroinclusion, just like other areas of EDI, might seem overwhelming at the beginning. There is a fear of “not getting it right” or making a “mistake”. It is important to remember that inclusion is a journey, it is an everyday practice. It is not a box to be ticked. Every candidate is different, and each recruitment process is unique. There is no “one size fits all”.

That is why it is so important to remain humble and open minded. Have confidence to co-create the recruitment process with your candidates. They are experts in what might help them to succeed in the process. No one knows everything, so you should not put pressure on yourself to do so. Just keep on learning and build confidence to take meaningful action towards neuroinclusion. The glossary in the next tab (Glossary and key facts) is a great resource to start.

Below you will find working definitions to help develop the neuroinclusion conversation in the workplace. These definitions represent Uptimize’s own current working language, which is inspired and guided by both subject matter experts and community focus groups.

As language can be contested, it’s also important to respect individual preferences. Some people may prefer “person-first” language such as ‘I am a person with dyslexia’, for example, while others prefer the ‘identity-first’ format of ‘I am dyspraxic’. In this guide, we used the latter throughout, though it’s best to remain alert to individual preferences. It’s always good to check if you are uncertain about which type of language to use with a neurodivergent colleague or candidate.

Neurodiversity

Neurodiversity means human brains are wired differently in terms of information processing, communication, and sensory processing.

Neurodivergent

While all brains are different, having certain characteristics can contribute to a shared identity with others or lead to a medical diagnosis: for example, an identity as autistic or diagnosis of ADHD. It is estimated that around 1 in 5 people may identify as having one or more of these neurodivergent identities. The term "neurodivergent" has entered the mainstream as a short hand for this large and varied group, many of whom possess multiple (neuro)identities and who are represented across all age, gender, ethnic and cultural groups.

Neurotypical

A common use of this term is for someone who doesn’t consider themselves neurodivergent. However, neurotypicality is contextual: an autistic person in a team with many other autistic people would probably not consider themselves atypical in that context. Modern workplaces and hiring processes tend to be geared towards people with the most commonly occurring preferences and traits which can lead to norms that disadvantage others.

Neuroinclusion

Neurodiversity inclusion or "neuroinclusion" involves consciously and actively including all types of information processing, learning, and communication styles.

Masking

A process by which an individual changes or "masks" their natural way of being to conform to societal pressures and norms.

Key Facts about neurodiversity at work

|

Share this article